India’s T-Series built an online empire from Bollywood. Now it has to survive Netflix.

On a recent afternoon in the Arabian Desert, with the temperature hovering around 40C, the cast and crew of Street Dancer 3D are trying very hard to pretend they’re in London. Starring two of Bollywood’s biggest young stars, Varun Dhawan and Shraddha Kapoor, the movie tells the story of rival dance crews facing off on the British capital’s mean streets. But because of the tiresome bureaucracy required to close actual London streets to blast Bollywood music for 10 hours at a time, the dance battles are being shot outside Dubai, in a theme park’s mock French village.

To create the illusion of a London neighbourhood, or at least a South Asian audience’s idea of one, the crew has strung Union Jacks across the village square and parked an array of borrowed sports cars on the cobblestones. Multicultural extras are wilting in the hoodies and coats they’re wearing to ward off the nonexistent English chill, and makeup artists are working furiously to hide everyone’s sweat. Between takes, a small man with a tote bag rushes in to shade Kapoor under an umbrella.

As cinematic visions go, it all seems a little strained. But when the cameras roll, and the catchy flute loop of a Punjabi rap anthem gets going, Street Dancer 3D’s producer gleefully shimmies his shoulders. “These kinds of visuals—I am getting value for my money,” says Bhushan Kumar, a 41-year-old with a pompadour and a soft, boyish face. He’s clad head to toe in designer brands: Tom Ford glasses, Burberry T-shirt, Palm Angels sneakers. With the director at his side and his entourage all around, Kumar reclines in a folding chair, the picture of a man satisfied with what he sees. “It’s a good-looking location,” he says. “They’re getting great dancing with great actors. It has all the things that matter a lot.”

When it comes to entertainment, Kumar has a better claim on knowing what matters to India’s 1.3 billion people than almost anyone. The head of T-Series, the country’s largest record label, he’s the custodian of a catalog of Bollywood soundtracks, Tamil pop tunes, and devotional music that accounts for a huge proportion of listening in the most music-crazy country on the planet. Since music and film are inextricably linked in India—almost all major hits come from soundtracks, and elaborate dance routines are the centrepiece of movies in almost every genre—Kumar is also a crucial cinematic tastemaker. T-Series’ in-house production arm has put out more than a dozen releases in the past year, including Kabir Singh, the second highest-grossing Bollywood title of 2019, with about $39 million in box-office revenue.

In February the company achieved another milestone: It became the world’s most popular YouTube channel, dethroning Swedish gamer-troll PewDiePie. The ascent of T-Series, which has 117 million subscribers to its primary feed, caught many off guard. YouTube has been dominated by pranksters, vloggers, and beauty queens from the U.S. and Europe. No professional media producer, let alone one from Asia, had ever held the top spot. But thanks to low-cost broadband access, India is now the largest source of consumers on the open web, with more than 600 million people online. (China has more internet users, but they generally stay behind the walls of its sealed-off digital ecosystem.) And that still represents a market in its infancy—about half of India’s population doesn’t yet have internet access.

Eager to cash in, Netflix, Facebook, and Amazon are all pouring resources into India and introducing products there before rolling them out elsewhere. In July, Netflix Inc. chose India to offer its first mobile-only subscription, an option that will be critical to unlocking emerging markets. Facebook wants to use the country as a test bed for payments via WhatsApp.

For Kumar, the internet giants’ newfound interest is both a threat and an opportunity. With bigger budgets and fathomless technological assets, foreign companies might pose a serious challenge to Indian producers, peeling away talent and eyeballs while threatening the Bollywood hit factory that underpins his success. Or they could be valuable partners, eager for the intimate knowledge of the Indian market that only a company like T-Series can provide.

Kumar believes it’s the latter. He envisions a self-reinforcing ecosystem where his YouTube channels promote his songs, his songs promote his movies and digital TV series, and when those become hits, people go back to YouTube to listen to the songs again and again, putting T-Series in an unassailable position. And with Bollywood content growing steadily more popular in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and other markets, that could make the company a global player, too.

“All over the country, you ask anyone if they know T-Series, they will say yes,” Kumar says in an interview in Dubai. Soon, he adds, “everyone will know us all around the world.”

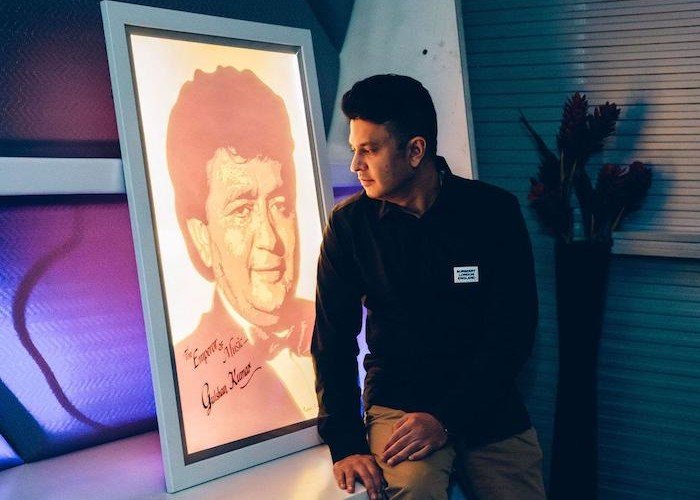

Kumar credits his late father, who founded T-Series, with all of its success. Gulshan Kumar was murdered in 1997, shot 16 times as he exited a Hindu temple in broad daylight—reportedly for resisting an extortion attempt by a gang linked to Dawood Ibrahim, Mumbai’s most notorious underworld boss. Kumar refers to Gulshan in the present tense and says he believes his father is guiding T-Series from the afterlife; every film still opens with a title screen reading “Gulshan Kumar Presents.” Kumar attributes his most precious talent, his “ear sense” for picking hit songs, to his dad.

Another trait Kumar seems to have inherited is technological foresight. In his father’s day, the medium of tomorrow was the cassette tape. Gulshan, whose own father was a Delhi juice vendor, opened a small shop stocking water-misting fans and other gizmos in the 1970s. A lifelong music lover, he also tried selling albums and experimenting with production on tape, hiring singers to record songs about his favorite Hindu shrine. When his cassettes began to outsell the fans, Gulshan traveled to Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea to learn more about the technology. He returned with a deal to import magnetic tape, and in 1980 he set up a factory to assemble cassettes, many featuring music from a studio he built out of his early forays into recording.

Gulshan brought a disrupter’s sensibility to the business, offering tapes at deep discounts and distributing them through convenience stores and corner stalls. He commissioned albums in regional languages such as Punjabi and Bhojpuri, tapping markets competitors considered too small or fragmented to bother with. Along the way, he developed a reputation for playing fast and loose with the copyrights protecting India’s most popular songs, the ones from Hindi cinema’s “masala musicals”—mashups of action, comedy, and romance. T-Series denies that Gulshan ever engaged in outright bootlegging, but it doesn’t dispute that he exploited a copyright loophole permitting cover versions of hits.

Gulshan’s distribution network put him in an excellent position to get into Bollywood soundtrack production, and in the mid-1980s he founded T-Series—the “T” an homage to the god Shiva, who’s usually depicted carrying a trident. In 1990 the label catapulted itself to the top ranks of the industry by releasing the soundtrack for the musical romance Aashiqui, which remains a bestseller. Gulshan also began aggressively snapping up the rights to Bollywood soundtracks T-Series hadn’t put together; film producers were often happy to part with them, since the company’s marketing footprint increased the odds a song would become a hit and drive box office sales. Gulshan loved film as much as he loved music, so T-Series also built a business producing its own movies.

Bhushan Kumar refuses to speak about Gulshan’s murder, except to say it made him rethink his career plans. At 19, he took the company’s reins. “I knew what this business meant to my father,” he says. “I had to fulfill his dream. Any son’s job is to make his parents happy; that’s what I did.” To stabilise T-Series, he decided to focus primarily on music, accelerating his father’s song-buying strategy. Komal Nahta, a film industry analyst, estimates the company now holds the rights to as much as 70% of the Bollywood music released in the past three decades. At first, this business model looked fairly eccentric. For every big winner, T-Series was left with thousands of tracks gathering dust. After all, in the pre digital era even the most music-mad Indians were only going to buy so many albums.

In the developed world, the recent history of the music business goes something like this: Everything worked well until 1999, when a teenage coder named Sean Parker co-founded Napster, the first file-sharing service to achieve broad popularity. The ensuing golden age of piracy nearly wiped out the industry. Then Apple’s iTunes established a market for legitimate digital music and prepared the ground for Spotify and other streaming services.

In India, things went a little differently. While piracy was widespread, iTunes never got much traction. Instead, people bought ringtones. Westerners might remember these as an oddity of the early aughts, snippets of songs bought directly from a carrier such as Verizon or AT&T; they went out of style once the iPhone provided more interesting things to do with a mobile device. For Indians, they were a sensation, offering a cheap and accessible means to obtain popular music legally. As mobile phones made inroads among the middle class, having the right ringtone, purchased for as little as 10 rupees (14¢), became an essential symbol of personal style.

In 2003 a local web portal offered Kumar $500,000 for the right to scrape ringtones from the T-Series catalog. He said no and instead began playing telecom operators and ringtone aggregation companies—a thing, in India—against one another for ever-larger licensing fees. His passion for the format was unmatched. Kumar “used to work on every ringtone,” says T-Series President Neeraj Kalyan, who’s headed the label’s digital division since its 2003 creation. “He used to make multiple cuts of every song so you’d have your first stanza, your second stanza, every stanza of a song.” Each would be available as a separate ring. By the late 2000s ringtones were the music division’s largest revenue stream.

As this boom was nearing its peak, T-Series noticed bootlegged versions of its songs popping up in a very different format: YouTube. The company’s relaxed attitude to copyright law didn’t extend to American digital titans, and in 2007 it sued for infringement. The eventual settlement required YouTube to train T-Series to put its own videos on the site—and to provide generous advances on revenue from the ads that would run alongside them.

T-Series uploaded its first YouTube video, the peppy dance number Laung Da Lashkara, in 2011, just as ringtone sales were tailing off. It featured the stars of the film Patiala House, Akshay Kumar and Anushka Sharma, cavorting in full Indian formal wear through a chandeliers ballroom, accompanied by troupes of backup dancers in turbans. Like a final transmission from an era that was about to disappear forever, it included an SMS code in the description below the frame, inviting viewers to set the song as their ringtone. The video was a hit, and it marked the beginning of an all-in bet on YouTube at a time when most record labels, whether in Santa Monica or Mumbai, still viewed it as an annoyance at best. T-Series immediately got to work uploading its entire catalog, available for free to anyone who wanted to watch.

Despite India’s vast size, it still offered a surprisingly small pool of consumers. With underpowered mobile infrastructure, conservative telecom carriers, and a huge number of people living below the poverty line, the country lagged behind much of Asia in smartphone adoption. Just a quarter of the population enjoyed mobile internet access in 2015. Going online didn’t became a truly mass-market phenomenon until the following year, when billionaire Mukesh Ambani launched a nationwide 4G network called Reliance Jio. Ambani gave Jio a long financial leash, allowing it to offer free voice calls and ultra cheap data plans. By its sixth month it had 100 million customers. Data prices fell to the lowest level in the world—about 26¢ per gigabyte, according to calculations by Cable.co.uk, which analyses the industry.

In all, about 300 million Indians have come online for the first time in the past three years. Compared with the 330 million who had access before, they’re generally poorer and less educated—and more likely to live in the rural hinterland than in Delhi or Mumbai. They skew young: 51% of India’s internet users are 24 or younger, with just 12% over 44, according to consultant Kantar IMRB. And while they practice half a dozen faiths and speak twice as many languages, they tend to have one thing in common. They love YouTube.

T-Series’ headquarters is located on the outskirts of New Delhi, in a cluster of buildings in the red and cream sandstone Indians associate with the Mughal Empire. The facility’s most important work takes place in a soundproof room deep inside. There, a portly man named Ganesh spends much of each day pulverising his eardrums with Bollywood tunes from two monster speakers, checking for distortion as each track is digitised for posterity. A heavily air-conditioned vault next door contains the fruits of his work, T-Series’ holy of holies: the bulk of the contemporary Bollywood songbook, 160,000 songs residing on 22 servers in five stacks.

YouTube popularity is essentially a volume game. Channels that upload videos more consistently get recommended and promoted more often, and people are more likely to subscribe to a channel with lots of new material. By tapping its back catalog alone, T-Series has been able to upload videos at a rate of two or three per day for most of the past decade. Its new songs are an even more reliable source of clicks, often preceded by teaser videos and followed by multiple tweaked versions to attract additional eyeballs. The label offers a wide array of tailored products, from audio-only tracks for users who want to burn less data to versions with English transcriptions, so non-Hindi-speaking fans can sing along, too. For devotional music, there are accompanying slide shows of gods and shrines and portraits of Gulshan Kumar looking devout.

The actual running of this online video empire requires remarkably few people. T-Series’ presence on YouTube and other streaming platforms is maintained by just 10 full-time employees, each responsible for uploading videos and songs in one language or genre. Kumar insists that T-Series’ digital popularity doesn’t owe simply to anticipating a technological shift or cannily managing its online presence. It’s all about picking hits. “An ear sense for music is the secret,” he says. “That’s the only reason we have achieved this kind of success on YouTube, because we are giving good quality music to our listeners.”

In Kumar’s telling, the components of quality haven’t really changed since his father’s era. To him there are only two types of music: “romantic songs,” which provoke an emotional response, and fast-paced “beat songs,” which get you dancing. Both need a hummable melody and catchy lyrics; from there, it’s just a question of garnishing the key ingredients with whatever vocalist, instrumentation, or technological flourishes happen to be in fashion. “That’s the thumb rule of a hit song,” he says.

It’s a lucrative strategy. T-Series, which still operates legally under the name Gulshan first incorporated, Super Cassettes Industries, isn’t publicly listed. But disclosures filed with the Indian government show that revenue jumped about 18.5%, to about $109 million, from 2016 to 2018—a period that wouldn’t fully capture the recent surge in YouTube subscriptions. In its 2018 financial year, it turned a profit of $29 million.

That performance, however, won’t spin off anything like the financial firepower that Silicon Valley is capable of bringing to India. The major streaming services are piling in as expansion slows in developed markets. Netflix, which will spend $15 billion on programming in 2019, has backed about 40 Indian films and series, betting that some of them, like the detective drama Sacred Games, will join the growing number of local titles that have crossed over to gain international success. Amazon.com Inc. is expanding aggressively, too. Indians now have more than 15 streaming platforms to choose from, some charging well under $1 a month.

Kumar argues that T-Series has no reason to fear this invasion, and not just because it sits behind a moat filled with more than 200 million YouTube subscribers. In recent years the company has doubled down on Bollywood, producing more than 24 films since the beginning of 2017. Two of its releases are among the top 10 earners at the Indian box office this year, led by Kabir Singh, the story of a gifted surgeon who descends into alcoholism after his girlfriend is forced to marry another man.

This track record, Kumar proclaims, should make T-Series the preferred partner for anyone seeking to figure out what Indians want to watch and hear. Kumar says he’s in talks to produce several digital series with Amazon and Netflix, who are “coming to me because they want series with music.” (Both companies declined to comment.) Although Bollywood makes more nonmusicals than it once did, winning Indian hearts still generally requires songs. “If a hit song comes on in a theater,” Kumar says, “the mass audience get so excited they throw money, just out of excitement.” He means this literally.

The ability to promote releases on the world’s No. 1 YouTube channel certainly boosts T-Series’ appeal to potential partners. Its rise on the platform was unprecedented. In July 2016 it had about 12 million subscribers, according to research provider Tubular Labs Inc. Within two years it passed 50 million, putting it in striking distance of PewDiePie. As the gap closed, many of YouTube’s biggest stars rallied to the defense of the controversial, racially insensitive Swede (real name Felix Kjellberg), posting videos imploring their own fans to subscribe to his channel. To urge them on, Kjellberg posted a diss track titled “bitch lasagna” that mixed chest-pumping bravado with casual racism. “I’m a blue-eyes white dragon while you’re just dark magician,” he rapped to his Indian rival. “Your language sounds like it came from a mumble rap community,” went a different verse.

Kjellberg held off T-Series for a while, but his relatively infrequent posts were no match for a well-oiled Bollywood juggernaut. After admitting defeat, he uploaded a mock-congratulatory video that made light of India’s caste system, suggested T-Series had colluded with organized crime, and revived allegations that it profited from pirated songs. It also identified the real reason for his loss. “All it took,” he said, “was a massive corporate entity with every song in Bollywood.”

There’s no predicting whether T-Series will retain Indians’ loyalty as their options for online diversion multiply. But to the millions of them for whom getting on the web was a life-changing transformation, the label’s primary platform is more or less synonymous with entertainment.

A visit to Dharavi, a sprawling slum that abuts Mumbai’s international airport, can illustrate why. Ismail Modan, a tall, moustachioed 39-year-old, lives there with his wife and two children in a second-floor walk-up with a cracking plaster facade. The family shares a single room of 180 square feet, neatly organized with a gas stove in one corner, a cot in another, and a single window looking out at the blank wall of the next building.

Until 2017 no one in the family had access to the internet. When smartphones started appearing in Dharavi, Modan, who earns about $200 a month selling surplus clothes from Mumbai’s malls, saved up to buy one. At $70, the used Samsung Galaxy J7 was a financial strain, but it quickly took center stage in his life. Previously, he had to go door-to-door to alert customers of new stock. Now he just updates his WhatsApp status, and the buyers come to him. Yasmeen, his wife, goes online to find designs for her tailoring business and recipes for the family.

An ancient cathode-ray television is still perched on a shelf above the cot, but it’s been largely replaced by YouTube’s unlimited library. The family huddles most evenings around Modan’s 5.5-inch screen to watch music videos and goofy viral clips. Other times, they hook up a Bluetooth speaker to play music from T-Series and other channels. Modan’s children, 10-year-old Rehmin and 14-year-old Manas, sing along. “We used to meet friends to pass the time,” Modan says with a smile. “Now we just stay home and watch YouTube.” —With Ragini Saxena